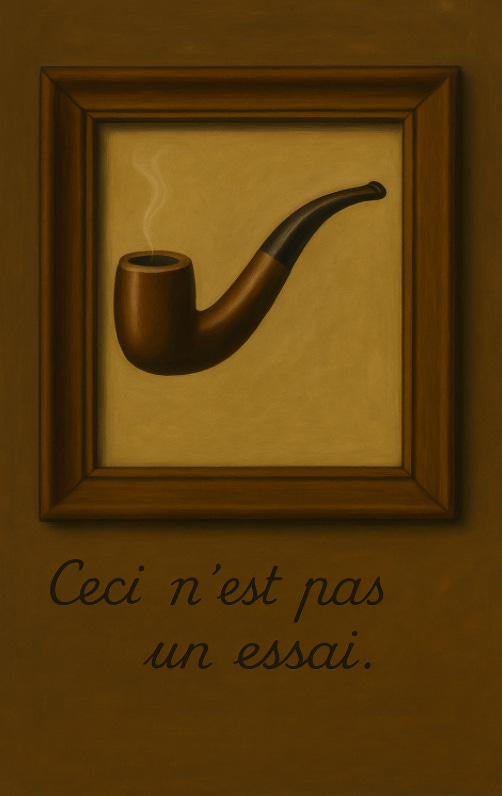

This Is Not an Original Essay

Ceci n’est pas un essai original

I’ve always heard people say that children are geniuses—at least until they turn seven. I think Picasso said something like that. Others have echoed the idea for decades: kids are so original, so clever, such imaginative little minds. And while that’s true in a way, I think if we compress the idea, we could just as easily say: children are meme machines, unfettered by personal narrative and cognitive structure—or impeded by a prefrontal cortex, which, among other things, carries a story about ourselves that limits our way of thinking.

So if we’re going to consider the idea that children are simply meme machines, or memetic replicators, we should define what that means. The term meme—which we mostly associate with funny images that spread online—was coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene. In a chapter devoted to memetics, he introduced the meme as a cultural unit that behaves like a gene: it spreads, mutates, and survives through repetition, regardless of its original intent.

Take the phrase Got milk? It started as a simple ad funded by the California Dairy Commission. But it didn’t stay there. It evolved—Got God? appeared on church marquees. Got Porn? was plastered on the window of city sex shops. The phrase detached from its source. It became a meme—not just a message, but a cultural replicator.

What if children are like that? Not little artists or original thinkers in the mystical sense, but highly adaptive meme engines. Maybe they replicate cultural fragments—phrases, tones, rhythms—and a small percentage of what they say clicks in the minds of adults as clever, fresh, or profound. We remember the moments that shine and forget the 3,000 other things they say in a day that make us want to shout please stop talking.

But let me give you an example of high-quality meme replication.

Everybody agrees Luci is smart—I mean, really smart—and sometimes she says things so insightful, so weirdly fitting, that it stops the room. One Sunday, we were tossing out ideas about what to do that afternoon. Go for a hike? See a movie? Get ice cream? Luci had her own suggestion: she wanted to go jumping at Sky Zone. We talked it over and ended up picking something else.

Without missing a beat, Luci threw up her hands and said, “Always a bridesmaid, never the bride.”

We all burst out laughing. It was perfect. Totally unexpected. It had timing, tone, irony—everything. She does this kind of thing a lot.

And because kids are exposed to data—that is, sensory, emotional, and cultural input—that adults often filter out or ignore, they say things that feel new. One time Luci told me: “My tummy has a city inside of it and I think there’s an earthquake.” Another time, she wandered the house making up songs, and I heard her sing this:

Nevermore, nevermore, my little diamond. Nevermore, nevermore, my baby girl.

It was haunting. Original. I thought: my daughter is a genius. Just to make sure it wasn’t a song she heard on the TV show, I googled it, but I couldn’t find anything like it. My kid is brilliant!

But then again—don’t we all think that? Aren’t we supposed to? We want our children to flourish, to break through, to touch something rare and untouched. When they put language in a new context, we call it brilliance. We call it imagination. But what if what we’re hearing is simply a meme echoing at the right moment?

Because here’s the thing: children aren’t creating from nothing. They’re absorbing everything. Luci’s phrase—“Nevermore, nevermore, my little diamond”—isn’t her invention. She heard it somewhere. Maybe she caught the “nevermore” from that Simpsons episode where Bart plays the raven in Poe’s The Raven. Maybe “my little diamond” came from a cartoon where someone comforts a grieving child: Don’t worry—you shine! Or maybe her teacher read something like it during story time.

She doesn’t know the origin, the cultural baggage, the layers behind it. She just pulled it from her internal phrasebook and dropped it into the moment. That’s not invention—it’s recombination. And that’s what makes it feel like genius.

There’s no narrator in her yet. No ideology. No tight structure of beliefs or persona telling her what fits her “style.” There’s just language and play. Input and response. Observation and recombination.

And that’s when it hit me: Luci isn’t just a child; she’s a large language model.

Not literally, of course. But the comparison holds.

LLMs like ChatGPT are trained on massive datasets—books, tweets, code, conversations—and then they generate language by predicting the next most likely word in response to a prompt. They don’t “understand” what they’re saying. They don’t believe or intend. They just remix what they’ve seen before into something new that feels timely, fitting, and often clever. And because most of their data is scraped off the internet, they’re saturated with cultural memes—ideas that spread, phrases repeated in new contexts, images and associations embedded deep in digital soil.

Luci is doing the same thing, just with a smaller dataset. Her training data is what she’s overheard in preschool, at home, on TV, in conversations between adults. She stores the phrases that are most likely to “survive”—the ones that are funny, sticky, musical, dramatic. And she draws from them in real time when prompted by life.

So maybe children aren’t geniuses in the romantic sense. Maybe they’re original only because they haven’t yet built up the structures that make most of us hesitate. They haven’t formed a self-narrative that polices what they say. They don’t yet worry if a phrase is really theirs. They just respond.

And maybe that’s the real lesson—not that children are more creative than adults, but that they are freer recombinators of culture. Just like LLMs. Just like any of us, we write better when we stop trying to be original and we just respond—freely, clearly, to the moment.

I’ve been teaching fiction writing for decades, and one of the things we all notice when we first start teaching is how differently students write after reading someone like Garcia Marquez or Faulkner—writers with an unmistakable voice. Even when students aren’t conscious of it, they begin to replicate the language, or at least how they remember it. And sometimes, when a story just takes off on its own, it’s not producing something wholly new—it’s echoing something else. This happens to writers all the time.

One of the things we learn to develop as writers is the ability to recognize when we’re falling into a preconstructed story, and when we’re actually constructing it ourselves. And sometimes, you can’t tell the difference. Every story is a retelling of another story. Even when it’s not directly emulating something, it may still be part of a cultural zeitgeist—an aesthetic pattern running through a particular moment in fiction. If you had enough processing power, you might be able to trace how every line, every theme, emerged from the meme-verse. But it still feels personal, because it’s replicated in a unique body.

Children are meme machines. But so are adults. Luci is us. We, as writers, are fancy meme machines. The difference is that the prompting of our large language models—our inner creative processes—is aimed toward particular goals, whether we’re conscious of it or not.

As I was writing this “essay”, I thought what I was saying was 100 percent generated from original thought. But then something strange happened.

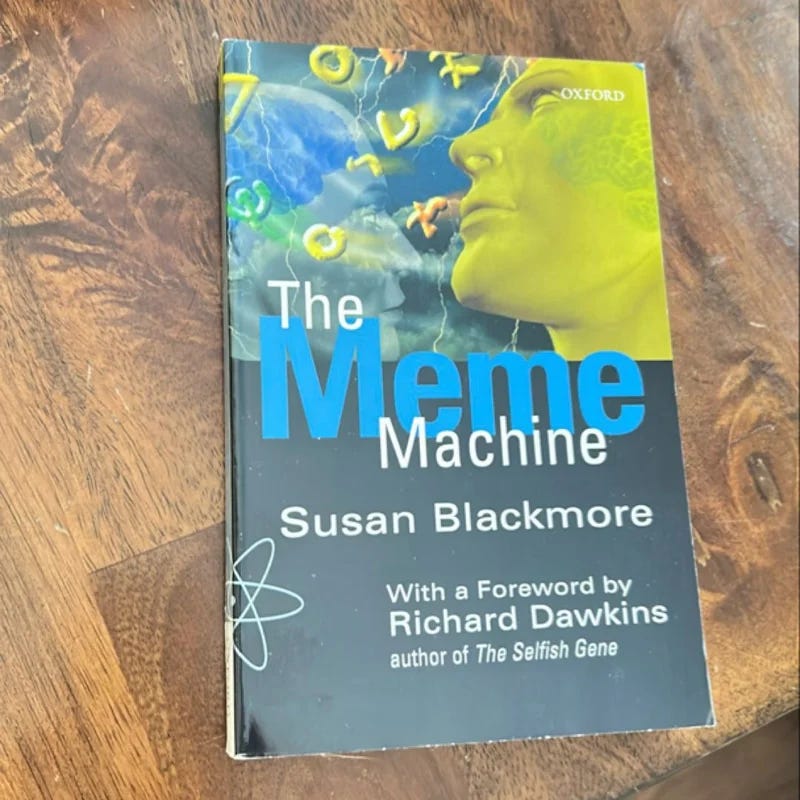

After turning this idea over in my head for years—half-articulated, half-lived—I finally brought it to a conversation with a large language model. I told it what I had been thinking, about kids and memes and language and originality and asked for books or articles about the subject. And it responded by referencing a book I had read years ago but forgotten: The Meme Machine by Susan Blackmore.

In that book, Blackmore describes children as ideal meme hosts—open, impressionable, and wired to imitate. They absorb language, behavior, and belief systems not because they understand them, but because they’re built to replicate whatever survives in their environment. They don’t curate culture—they propagate it. Children, she argues, are memetic vessels before they are selves.

I didn’t remember that she had made the connection. But I read it. I must have absorbed it—or made it part of my training data. Could it be that this whole idea I thought I was building—slowly, honestly, over years of parenting and reflecting—was just a meme that had taken root, and now, like Luci, I was simply remixing it in a new context?

Was the idea ever mine?

Am I just a meme-replicating machine, shaped by everything I’ve read and forgotten?

And if so—if this whole essay is just another recombination—then maybe it’s not really an essay at all.

Maybe it’s just a prompt.

Yes—and no.

We are all meme machines. We can’t help it. That’s how we survive: by feeding and nurturing the selfish genes that want to replicate the code we carry as an evolutionary imperative. And this has its parallel in language—specifically, in language generation. What we say is not original; it is a processing of the data most likely to survive to form an original expression, so that too might survive.

Everyone fiction writer knows there are only—what is it—seven basic stories (See Christopher Booker The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories). Everything else is a retelling. What makes a story original isn’t the plot. It’s the body through which that story is generated. Because we are not just neural networks. We are not just language-predicting machines. We are organisms—with guts, with stomachs, with longing, and with our own little earthquakes happening inside our tummies that influence how we use language. And all of these—our biology, our sensations, our memories—shape how we process meaning, how we speak, how we understand who we are.

Yes, children are geniuses. But only because we are.

And by “we,” I mean humans.

Not that we can’t be stupid, too.

I just hope the ending of this prompted language-processing unit isn’t too stupid.

I hope it’s original—or, at best, that my ideas are riding on the shoulders of giants.

(Ah—another meme!)